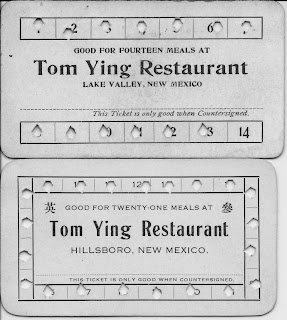

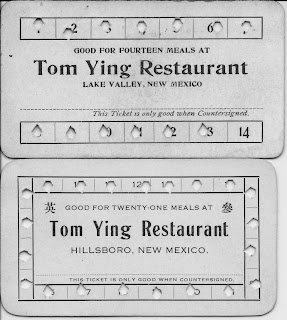

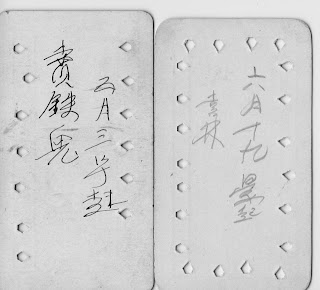

Two meal tickets from Tom Ying’s business are revealing for what they say in English—and Chinese. They are part of the collection held by the Black Range Museum, located in Ying’s old Hillsboro restaurant.

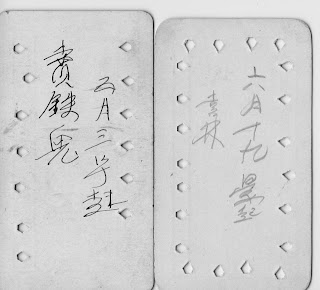

The older one is from Tom’s restaurant in Lake Valley and unless he ran two restaurants at the same time in two different localities, it must date from before 1896 when Sadie Orchard hired Tom to run the restaurant of her Ocean Grove Hotel in Hillsboro, the present-day Black Range Museum. On the back of this ticket, which has one meal left on it, Tom has written in Chinese the date when the ticket was validated. It reads: “wu yue san hao qi” or “begin May third.” No year is given. And, Tom has written the name of the person who bought the ticket. This “name” is not a Chinese name, and so it must refer to some American, whose name, of course, could not be written in Chinese. It’s what Tom called him in his own mind to identify his customer. Tom wrote “mai tie gui” or “the whitey who sells iron.” So, this ticket belonged to an ironmonger or perhaps the village blacksmith in Lake Valley.

|

| Meal tickets used by patrons of Tom Ying's restaurants in Hillsboro and Lake Valley. Black Range Museum |

The word I’ve translated as “whitey” is “gui,” and it means ghost or spirit or devil or any otherworldly, somewhat scary phenomenon. The 19th century Chinese commonly called Europeans and Americans “gui,” and it was rendered by Americans as “foreign devils.” It is a term with a lot of racist overtones. Considering that Tom was regularly called in Hillsboro “the Chinaman,” as in “the Chinaman’s restaurant,” Tom’s bit of reverse racism seems perfectly fitting.

The other ticket dates from Tom’s Hillsboro days, that is, from after 1896. It has on the front Tom’s Chinese name: Ying Seng. Chinese put the family name before the given name. It’s a somewhat unusual name since Chinese given names are usually two syllables long, and whoever is responsible for this one syllable name, either his parents or himself if it was self-chosen, was a bit arty. It’s the word for the magical herb ginseng. When I first came to Hillsboro in the late 1980’s, Felipe Roybal gave me an unused Tom Ying meal ticket from the 1950s, and it does not have Tom’s Chinese name on it. I assume that Tom used his Chinese name only in the early days, when he felt closer to Chinese things and so I would think this ticket dates from the turn of the century.

On the back of this second ticket, Tom wrote the validation date: “liu yue shi jiu chen qi” or “begin the morning of June 19th.” Again, it has no year. Tom has also written what he called the owner: “xi lin.” Who could this have been? “Xi lin” may have been Tom’s attempt to sound out some American name with Chinese sounds. Most likely, Tom was Cantonese and would have pronounced these words something like “hei lum.” Was there a Hiram around? But “xi lin” means “happy trees” and so it might refer to someone living in Happy Flats, as the eastern section of Hillsboro is called, who had some trees on his land. Or, does it refer to someone related to the Ocean Grove Hotel? Or, is this the meal ticket of Sadie herself, whose name we recall was Orchard, the happy orchard, though we’d have to assume that Sadie didn’t need to have a punch ticket.

|

| What Tom Ying wrote on the back of the meal tickets raises more questions than it answers. The card are oriented the way Tom would written on them, vertically. Black Range Musuem |

These tickets give us some pieces in the puzzle of the past, but, as usual in historical research, they point us to gaps we didn’t even know existed. Not only do we not know who the Lake Valley ironmonger was or who Tom called “happy grove,” but we don’t really know Ying Seng himself. Some in Hillsboro still remember him from their childhoods. He was an old man who sat outside his restaurant and gave kids candy. He died in 1959, and was buried up in the cemetery. His stone had no dates. Now there is a bronze plate with the dates 1849—1959, which has been covered by another plate with the dates 1866—1959. The Mormon Church’s genealogical records has Tom listed with a birth year and place as 1850 in Hillsboro, NM. I’m sure Tom himself did not know his birth year in Christian numerical form since he would have had to memorize all the Chinese names of years in proper sequence and count back to his birth year’s name to calculate the Christian year. Regardless, Tom he must have come to this country before the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act which banned Chinese from immigrating to the U.S. from 1882 until the Act’s repeal during WWII.

Since he never married, it seems likely that he left a family in China, and the Exclusion Act doomed him, like thousands of other unmarried Chinese men in the U.S., to a solitary and lonely life.

– Max Yeh