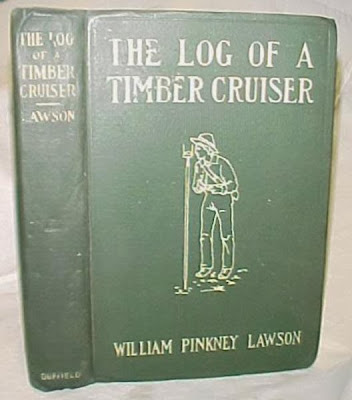

Writer William Pinkney Lawson spent several months on the crest of the Black Range measuring trees for the nascent Gila Forest Reserve, today's Gila National Forest, circa 1912. He turned the experience into a book, The Log of a Timber Cruiser. It was published in 1915.

Though Lawson spent most of his time in the woods high in the Black Range, he writes about a murder in Hillsboro, his observations of an abandoned Kingston, and about some of the personalities he met along the way. Founder of the Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, called the book a "real record of real things."

Some of those real things including being treed by a mountain lion, facing the harsh elements, catching Gila trout, and getting cleaned up for a fandango and meeting girls at ranch on Black Canyon.

This is a must-read for a look into life a century ago. You can read the book online. Be sure to type in some local place names in the search box to read what Lawson saw. If you want a copy of your own, try Hillsboro bookseller, Aldo's Attic.

--Craig Springer

December 4, 2013

November 27, 2013

November 23, 2013

Kingston Plat 1887

The General Land Office surveyed the Kingston townsite in 1887. The town was five years old. The resulting map illustrates where commerce was centered--and no surprises, on Main Street.

The General Land Office surveyed the Kingston townsite in 1887. The town was five years old. The resulting map illustrates where commerce was centered--and no surprises, on Main Street.The plat shows the position of mining claims that coincide with the townsite, that is, the mining interests beneath the town. The smelter site was on the north edge of town.

|

| Kingston, 1887. |

The map has another value in showing us today the siting of two businesses, the Printing Office and Photo Gallery, located next door to one another on the west end of town on the north side of Main. Look for lines surveyor's lines and notation that run northwesterly. The gallery was most likely owned by the prodigious photographer J.C. Burge. A good many of his images are archived at the New Mexico History Museum and viewable online.

A couple of curiosities come to the fore looking at the town plat, and the another map of the entire 36-square-mile township map. One, the townsite is rather small; it's only 240 acres. Something else of note, the buildings are few.

| T |

If you would like to see the maps in their entirety, click on these links.

Kingston's 240-acre townsite plat map, 1887.

Kingston township map, 1889.

--Craig Springer

November 19, 2013

Kingston through the Eyes of a Reporter - 1882

Kingston sprung from the wilderness with the finding of silver float. The townsite was platted in the latter part of 1882. The mining activity drew much attention from prospectors, capitalists -- and reporters.

One such journalist writing for the Lone Star offers us a very early glimpse into the economy and life style of the nascent mining camp called Kingston. The writer remarked on title issues associated with the town's lots. Witness this curious remark: "One woman has taken a lot and built on it and refuses to pay for it. She is not being molested."

The story was reprinted in the October 28, 1882 Lincoln County Leader, published in White Oaks, New Mexico. -- Craig Springer

| Lincoln County Leader, October 28, 1882. Library of Congress |

One such journalist writing for the Lone Star offers us a very early glimpse into the economy and life style of the nascent mining camp called Kingston. The writer remarked on title issues associated with the town's lots. Witness this curious remark: "One woman has taken a lot and built on it and refuses to pay for it. She is not being molested."

The story was reprinted in the October 28, 1882 Lincoln County Leader, published in White Oaks, New Mexico. -- Craig Springer

November 15, 2013

Gavilan Trail 1889

This portion of the 1888 township subdivisional survey plat map shows Gavilan Trail heading over the pass in the Mimbres Mountains. This is likely the trail taken by the U.S. Cavalry and posse on Nana's tail in August 1881.

This was a well worn path. Stephen Watts Kearney and the Army of the West, with Lt. Emory, guided by Kit Carson passed this way in October 1846. In fact, they camped one night a few miles downslope to the east along Berrenda Creek. Harley Shaw in a previous post on Hillsboro History referenced the published journals of soldiers who made the trek in the Mexican War. Emory Pass was not used by Kearney, though it commemorates his army's endeavors.

The headwater stem of Macho Creek in sections 30 and 31 is now known as Pollock Creek in memorial to Brady Pollock who was murdered by Geronimo in September 1885.

On the full version of the map, those familiar with the history around Hillsboro, Kingston and Lake Valley will recognize some of the names on the map, those like Knight, Richards, Parks, and Latham. Parks Ranch, too, is associated Apache depradation. Ranch hand Jacob Hailing was murdered in Ulzana's Raid of November 8, 1885. -- Craig Springer

This was a well worn path. Stephen Watts Kearney and the Army of the West, with Lt. Emory, guided by Kit Carson passed this way in October 1846. In fact, they camped one night a few miles downslope to the east along Berrenda Creek. Harley Shaw in a previous post on Hillsboro History referenced the published journals of soldiers who made the trek in the Mexican War. Emory Pass was not used by Kearney, though it commemorates his army's endeavors.

The headwater stem of Macho Creek in sections 30 and 31 is now known as Pollock Creek in memorial to Brady Pollock who was murdered by Geronimo in September 1885.

On the full version of the map, those familiar with the history around Hillsboro, Kingston and Lake Valley will recognize some of the names on the map, those like Knight, Richards, Parks, and Latham. Parks Ranch, too, is associated Apache depradation. Ranch hand Jacob Hailing was murdered in Ulzana's Raid of November 8, 1885. -- Craig Springer

November 11, 2013

Veterans of Hillsboro

In keeping with this remembrance of veterans, here's a vignette of a former Hillsboro resident, the late Ernest Springer, who lived through the historic Heart Break Ridge battle in North Korea, September - October, 1951. Some Hillsboro, Lake Valley, and Kingston residents might remember him for his long walks.

Springer is only one of several Hillsboro-area men and women who served in the military. Hillsboro's earliest, and in fact very first residents, were veterans of the Civil War, men like Joseph Trimble Yankie, David Stitzel, James Porter Parker, and General C.C. Crews. The first two were Union soldiers, that latter two were Confederates.

|

| Reenactors commemorate General C.C. Crews, at his grave in Hillsboro. |

Springer is only one of several Hillsboro-area men and women who served in the military. Hillsboro's earliest, and in fact very first residents, were veterans of the Civil War, men like Joseph Trimble Yankie, David Stitzel, James Porter Parker, and General C.C. Crews. The first two were Union soldiers, that latter two were Confederates.

A Tale of Two Canyons

Mark B. Thompson, III

It seems fair to state that my great-grandfather, and Hillsboro, New Mexico politician, Nicholas Galles, was undoubtedly proud of his association with what I would call the defense against the Apache insurgency, 1860-1886. For example, both a 1902 Santa Fe New Mexican article, and his 19ll obituary in The Rio Grande Republican published in Las Cruces mention his involvement from 1877 through 1886. I have previously written that by time of the 1902 newspaper article he was certainly not “trumpeting” his involvement in the 1885, Geronimo, campaign. I decided to take a closer look at the 1881 encounter with Nana.

As described in the Saturday, August 27, 1881, edition of The Rio Grande Republican, Galles was reported as “missing in action” after the August 19, 1881, battle with the Apaches: “Mr. Elias Blain of Hillsboro, who arrived here last Sunday furnishes the Republican the particulars of the fight at Gabilan cañon, between Lake Valley and Georgetown, a brief account of which was given in last Saturday’s Republican. [Note: Phonetic spelling of Gavilan and Spanish for canyon in original.]

“It appears the Indians rode right into Hillsboro and from a hill overlooking the town fired into the houses. Lt. G.W. Smith, with twenty troops and thirty-five merchants and miners of Hillsboro and Lake Valley started in pursuit of the Indians and when passing through Gabilan cañon, nine miles from Lake Valley, they were fired upon by the Indians concealed in the rocks. They were completely surprised and Lt. Smith and Mr. Daly and three soldiers were killed and four soldiers wounded. The troops and citizens scattered and twelve of the most prominent citizens are still missing, among them Mr. Nicholas Galles, one of the county commissioners of this county.” [Note: Hillsboro was part of Doña Ana County until Sierra County was created in 1884.]

Both the 1902 and 191l newspaper accounts arguably cover the story of 1881 but without a clear date reference. The Galles 1911 obituary describes a battle in Grant County which could be a reference to the August 1881 encounter because it states that Galles had his horse shot out from under him but that he was able to hide from the enemy for the rest of the battle, was missing for several days and thought dead until his reemergence. [Ironically, it was the report of his death in the New Ulm, Minnesota newspaper in September of 1881 that provided us with more background information on why the Minnesotan Galles had come to New Mexico about 1875.] The obituary, however, says that 65 soldiers and “militia” died in the otherwise unidentified encounter which clearly did not happened in August 1881. The 1902 New Mexican article merely states that Galles was “present” at the encounter in which Lt. Smith and George Daly were killed.

If that tale seems strange, the fact is that the civilians at “Gavilan Canyon” generally come off looking bad. Historian Charles L. Kenner, Buffalo Soldiers and Officers of the Ninth Cavalry, 1867-1898 (1999), pp. 225-31, claims that Lt. Smith knew he was to wait for reinforcements but that George Daly called him a coward and threatened to lead the civilians out of Lake Valley in pursuit of Chief Nana and the Apaches with or without the cavalry. Kenner says that when the cavalry entered the canyon at 9:30 A.M. on the 19th with the “motley train of miners and cowboys,” many of the civilians “were still drinking.” He says that after Smith and Daly were killed in the opening salvo, “the miners either fled madly down the canyon or collapsed in fright behind boulders.” Historian Frank N. Schubert, Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and the Medal of Honor, 1870-1898 (1997), pp. 76-89, says that Lt. Smith knew better but had followed the “eager cowboys” into Gavilan Canyon and does not mention the “cowboys” continuing the fight after the initial killing of Daly.

| Battles between Buffalo Soldiers and Apaches in NM made national news. |

One of New Mexico’s earliest history writers, Ralph Emerson Twitchell, apparently thought this was a story about the leadership of John B. McPherson, a Hillsboro merchant and saloon keeper. Twitchell claims that McPherson was the leader of a group of forty citizens who accompanied the troop of forty soldiers into “Gavalan [sic] Canyon,” misstating the date, but mentioning the deaths of Lt. Smith and George Daly. The Leading Facts of New Mexican History (Vol. 2, 1912), pp. 438-39, n. 359. No other historian or history writer mentions McPherson and I suspect that McPherson’s living in Hillsboro until his death there in 1921 may have something to do with Twitchell making him the leader, when all others seemed to think it was George Daly.

Both Kenner and Schubert rely upon a documents found in the Medal of Honor files, documents available on microfilm at the National Archives & Records Administration in Washington D.C. or at three regional offices, but not the office in Broomfield, Colorado. I am guessing that Lee Silva, in his essay, “Warm Springs Apache Leader Nana: The 80-Year-Old Warrior Turned the Tables,” also made use of the Medal of Honor affidavits and reports. Silva makes sense of the story by stating that the group left Lake Valley shortly after midnight, having spent the evening drinking at a local saloon, and that the ambush took place at about 10:30 A.M. He states one or two other civilians were killed and that George Gamble of Lake Valley, like Nicholas Galles, was also late getting back home and only after Gamble’s spouse had been told that Gamble was dead.

Lee Silva also deals with what is a “major distraction” with this story, where did the ambush take place? The original reports of the Army talk about “Gavilan Pass,” “Cavalaus Canon,” probably a misreading of a Spanish name, and “McEwer’s Ranch,” undoubtedly a misspelling of an early name for Lake Valley, McEvers Ranch. Historian Dan L. Thrapp, The Conquest of Apacheria (U. of Okla. 1967), p. 215, places the ambush at “Guerillo Canyon, fifteen miles from McEver’s Ranch.” Because there is no Guerillo Canyon on modern maps or in the USGS place name tables, I have no idea where he came up with that story. A more serious “problem” is that there is also no “Gavilan Canyon,” the name most often used in the histories, often misspelled and sometimes using the Spanish name. [“Gavilán” is Spanish for “sparrow-hawk,” but has other meanings and uses.]

Silva describes a route to “Gavilan Canyon” that probably would have taken about ten hours from Lake Valley and would be consistent with his story that the posse and Cavalry left the saloon shortly after midnight and encountered the Apaches about 10:30 AM. Just as importantly, Silva’s description is more or less consistent with the August 27th newspaper account putting the event about nine miles west of Lake Valley. Silva has the group going north to Berrenda Creek, then west to an unnamed spot, then south to Pollock Creek, which could then be followed almost to the summit of the Mimbres Mountains, then over the mountain (and the Grant/Sierra county boundary today) to Dry Gavilan Creek. The map below, courtesy of Gary O’Dowd, outlines what that route might have looked like. But some questions, given all of the factors described by Silva, still exist.

|

| Potential route taken by Nana, posse, and Cavlary from Lake Valley, over the Mimbres Mountains, August 1881. Courtesy Gary O'Dowd |

If this is a story of not just two but multiple canyons, it is also a story of at least two tales with the second being the more important. As you might have guessed, the second tale is what happened after Lt. George W. Smith was killed in opening minutes of the ambush. Both Kenner and Schubert, as well as Silva, tell us the story of the African-American “Buffalo Soldier” Brent Woods and how he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at “Gavilan Canyon.” See also, Bob Barnes' excellent portrayal in a “Tale of Lake Valley.”

Although these authors of “military history” vary somewhat in the detail, they all explain how Brent Woods rallied the troops after the death of Lt. Smith and held off Nana and the Apaches for several hours before Nana decided that the better part of his valor was to abandon the fight. Another “side bar” story concerns the fact that it took the Army until 1894 to recommend Woods for the Medal of Honor. Kenner concedes that the contemporary Army record of Gavilan Pass barely acknowledges Woods valor. Schubert notes that, in reviewing the medal proposal in 1894, Major General John M. Schofield questioned the absence of contemporary reports on Woods and Gavilan Canyon but eventually decided the post-1881 evidence was persuasive. In reporting the awarding of the medal, The Washington Times on July 14, 1894, says it was awarded “By direction of the President.”

|

| Buffalo Soldier and Medal of Honor recipient, Brent Woods, is honored at the New Mexico Memorial Garden in Albuquerque. Mark B. Thompson photo |

In addition to the sources cited above, Wikipedia has an article on Brent Woods, and there are several photos online, most probably taken at or near the time he was awarded the medal. When he died in 1906 he was not given a military funeral nor a veteran’s grave marker and it was only in 1984 that his remains were reinterred in the Mills Springs National Cemetery in Kentucky. In 2011 he was honored by the creation of a statue now standing in the New Mexico Veterans Memorial Gardens in Albuquerque. I could be wrong, of course, but it seems to me that the “Buffalo Soldier” awarded a Medal of Honor for his bravery in an encounter with the Apaches in 1881 is largely ignored in New Mexico history.

March 19, 2013

Francisco Bojorquez: The Cowboy Sheriff of Sierra County

Saturday, April 13, 3:00 p.m., at the Hillsboro Community Center

Presentation by Karl W. Laumbach

Sponsored by the Hillsboro Historical Society

Francisco Bojorquez (l) with Hillsboro banker Gillespie

Francisco Bojorquez is a fading legend in the memories of old timers in Sierra County. Born in California, the son of Spanish émigrés, Bojorquez was raised in Sonora where he learned the skills of a vaquero.

Arriving in Sierra County in the 1880s, herapidly established himself as a top hand on local ranches and in regional "cowboy contests," where he pitted his roping and riding skills against the best cowboys in the Southwest.

The respect that made him foreman on large ranches employing Texas cowboys also propelled him into political office as county commissioner, state representative and finally, county sheriff.

Karl Laumbach, a graduate of New Mexico State University, spent nine years directing projects for the NMSU archaeology program before joining Human Systems Research, Inc., in 1983, where he currently serves as Associate Director and Principal Investigator for diverse projects. Among his varied research interests are northeastern New Mexico land grants, the pueblo archaeology of southern New Mexico, and the history and

archaeology of the Apache.

March 15, 2013

Nicholas Galles and the 1885 “Geronimo Campaign”

Mark B. Thompson, III

Almost ten years before his death, the Santa Fe New Mexican ran a front page article about Nicholas Galles on June 21, 1902, with the banner “Men of the Hour in New Mexico.” The article contained a long paragraph detailing his “five years” as a captain in the New Mexico Territorial Militia, the predecessor of the New Mexico National Guard, during the “Indian Troubles.” Surprisingly, the article did not mention his work in the 1885 campaign, probably the best documented of any of the Galles military experiences. Perhaps not surprisingly, this neglect of the 1885 events, not to mention the several other “errors and omissions,” were carried over into numerous obituaries after his death on December 5, 1911. Had Galles decided that “1885” was “no big deal?”

|

| N. Galles obit, 1911 |

On June 5, 1885, Galles wrote a letter* to New Mexico Territorial Governor, Edmund G. Ross, a former U.S. Senator from Kansas, later included in John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage for his part in the trial of Andrew Johnson for impeachment. This letter, accompanied by a petition signed by 36 willing volunteers, sought creation of a militia cavalry company for the Hillsboro area. They did not get a cavalry appointment, but on June 10, 1885, Galles took the oath of office as a captain of Company G of the 1st Infantry. (I wonder if they nevertheless rode horses?) The muster roll for Company G shows that 40 men in addition to Galles were enrolled, including the once and future Chief Justice of the New Mexico Supreme Court, Frank W. Parker, as well as the soon to be convicted felon, Julian L. (“Junee”?) Fuller. The four documents referred to can be found in the New Mexico Territorial Archives, together with a report from Galles which accompanied the eventual request for payment.

What prompted the June letter and what was the role of Company G in the 1885 campaign? Fortunately the original of the report was later read and “relied upon” in Washington, but the microfilm version is almost illegible. I believe we must turn to the historians, something we needed to do any way, to get the basic “facts.” The writers on the Chiricahua Apache “wars” are legion, and I have relied primarily on one recent publication: Edwin R. Sweeney, From Cochise to Geronimo: The Chiricahua Apaches, 1874-1886 (Norman: U. of Okla. Press, 2010). Sweeney does cite his sources in detail and each paragraph of his 580-page book is so crammed with facts that you almost have to outline each paragraph in order to have some confidence that you know what you just read. If not the last word on the subject, it certainly seemed like a good place to start.

Sweeney tells the 1885 story partly through the eyes of General George Crook of the U.S. Army. Sweeney, (p. 430), describes how on May 28, 1885, Crook left Prescott, Arizona to establish his field headquarters at Ft. Bayard, southeast of Silver City and west of Hillsboro, not knowing that Geronimo (and Chief Mangas) had left New Mexico for Mexico. Although the Galles letter to Gov. Ross is vague and general about the looming threat, it seems reasonable to assume that the prospective volunteers in Hillsboro were probably aware of Crook’s concerns and that Hillsboro might need to be defended. In fact, as described in detail by Sweeney, the focus of the story shifts to Mexico during the summer of 1885, but about September 5, 1885, it was determined that Geronimo was headed back into New Mexico (Sweeney p. 460).

At that point it was assumed that the Chiricahuas were probably headed to Ojo Caliente, north of Hillsboro, and the home of the Chihenne band before they were removed to the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. The first sighting was apparently in the Cooke’s range, the southern part of the Mimbres Mountains, about September 9, 1885. At that point neither U.S. troops nor militia were following Geronimo (Sweeney p. 462). On September 11, 1885, Geronimo’s men showed they were in fact traveling north when they attacked in several places, killing Brady Pollock near today's Pollock Canyon west of Lake Valley, then heading down Gavilan Canyon into the Mimbres drainage killing Martin McKinn and kidnapping his brother Santiago "Jimmy" McKinn. Geronimo then attacked further north in Gallinas Canyon, southeast of San Lorenzo. (Today you can roughly follow this path, and the Mimbres River, by traveling north on State Highway 61.) Finally, at least by September 12, 1885, the U.S. Cavalry from Ft. Bayard, militia from Hillsboro, and a small party of ranchers were in pursuit (Sweeney p. 464). Sweeney does not identify anyone in the militia from Hillsboro.

Sweeney says that Geronimo and his men spent the night of September 12, 1885, “near the confluence of Sapillo Creek and the Mimbres” (p. 464). Given the route Geronimo was taking toward the northwest, Sweeney could have meant either the confluence of Sapillo Creek and the Gila, or another creek on the Mimbres. Sapillo Creek is on the Pacific side of the Continental Divide and drains to the Gila. In any event, Geronimo now realized that he needed to put some distance between himself and the pursuers and by the evening of September 13, 1885, he had arrived at the Black Canyon, about eight miles southeast of the Gila Hot Springs. On Monday, September 14, 1885, the Apaches had reached the junction of Little Creek and the West Fork of the Gila. According to Sweeney, the army and militia at that point gave up the chase (p. 464).

Geronimo and his men made it to Arizona by September 19, 1885, but by September 27 they were back in New Mexico, killing a merchant, A.L. Sabourne, at Cactus Flat, about five miles northwest of Buckhorn. (Today U.S. 180 runs through Buckhorn.) Apparently they camped in that area for about a week and Sweeney relates that “Geronimo’s party left for Mexico about October 6, 1885” (p. 471). As we shall see, the period between the September 27 and October 6 is important for the Galles story, but Sweeney does not give any indication that Geronimo had moved east toward Hillsboro from Buckhorn during this period.

Perhaps because Congress passed another pension provision for veterans (and widows) of the “Indian Wars” on March 4, 1917, the widow of Nicholas Galles, Harriett Stocker Galles, filed an application for a widow’s pension on January 12, 1918. The application said that Galles had served in the territorial militia “in 1885 and perhaps 1886.” This application was rejected on March 5, 1919, on the grounds that the “muster rolls in the State Archives fails to show the period of service.” The records in Santa Fe were eventually found and apparently a request for “reconsideration” was filed with the federal authorities. A preliminary decision was made on August 29, 1923, indicating that the service was “pensionable if period of 30 days is shown.” By November 13, 1923, it was determined that the period of service was only eight days, from September 30, 1885, through October 7, 1885, and a final decision rejecting the application was issued on August 26, 1924. Harriett Galles filed yet another application in June of 1927, but it does not recite any additional facts.

|

| Harriet Stocker Galles |

The dates of September 30 through October 7 are consistent with a return of Geronimo to New Mexico on September 27 and his leaving for Mexico on October 6. It would make sense that the militia was “activated” on the September 30 because of the possibility of Geronimo moving toward Hillsboro, but, as we know (or believe), he stayed to the southwest of Hillsboro and then soon moved on to Mexico. What about the period of September 12, 1885 and September 14, 1885, when the militia had joined in pursuit of Geronimo up the Mimbres, etc? Was the militia, referred to by Sweeney, in fact Company G headed by Galles? As a matter of law, adding three or four days to the eight used for the pension application would have made no difference on the pension decision—it was still short of the required 30 days of service.

Even if the record had shown two-plus weeks of “active duty” during the 1885 campaign, Galles may have concluded that it was nothing to “brag about.” Sitting around and a few days chase on horseback obviously resulted in no encounter with Geronimo. Given the inclination of politicians to trumpet their “Indian Fighter” status, the absence of any mention of 1885 in the 1902 Santa Fe New Mexican article should give us pause. I have not confirmed that Galles served five full years as a captain in the militia during the period 1877-1882, as alleged in the 1902 article. There is, however, evidence of his participation in encounters with the Chiricahuas in 1879 and 1881, both of which, with mistakes, etc., are recited in the 1902 article and the subsequent obituaries. Geronimo was, and still is, the big name in this genre, but Galles may have decided it was better not to embellish his limited involvement in the 1885 encounters.

*You can read the referenced 1885 letter to Ross is the book, Around Hillsboro.

January 23, 2013

The Pancho Villa Connection

It's a storied invasion. Pancho Villa brashly attacked Columbus, New Mexico in 1916, killing several civilians, opening the wrath of the U.S. Army led by General Pershing.

And there is a Hillsboro connection.

Druggist C.C. Miller, originally from Kansas, went to Columbus after pulling up stakes in Hillsboro. C.C. Miller sold his drugstore business to George T. and Ninette Miller (no relation that we know of), and in that family the business remained until the early 1970s, when their son, George A. Miller passed away. Today, the building is the Country Store and Cafe.

C.C. Miller left a vacancy in the hearts of friends and family. His friend, Dr. Stivinson, survived the attack, and had this to say: "We found the body of our good friend, C.C. Miller, the druggist, lying in the door of his store . . . Mr. Miller had been a particularly fine character."

Part of the connection to Hillsboro is still tangible in the holdings of the Black Range Museum. The museum has C.C. Miller's pharmaceutical certification, dated 1885. Be sure and visit the museum to see this gem and many others. It's a privately owned museum, and your donations are encouraged and appreciated.

|

| Editorial cartoon 1916 LOC |

And there is a Hillsboro connection.

Druggist C.C. Miller, originally from Kansas, went to Columbus after pulling up stakes in Hillsboro. C.C. Miller sold his drugstore business to George T. and Ninette Miller (no relation that we know of), and in that family the business remained until the early 1970s, when their son, George A. Miller passed away. Today, the building is the Country Store and Cafe.

C.C. Miller left a vacancy in the hearts of friends and family. His friend, Dr. Stivinson, survived the attack, and had this to say: "We found the body of our good friend, C.C. Miller, the druggist, lying in the door of his store . . . Mr. Miller had been a particularly fine character."

Part of the connection to Hillsboro is still tangible in the holdings of the Black Range Museum. The museum has C.C. Miller's pharmaceutical certification, dated 1885. Be sure and visit the museum to see this gem and many others. It's a privately owned museum, and your donations are encouraged and appreciated.

| C.C. Miller's Kansas pharmacy certification. Miller, a former Hillsboro druggist, was murdered by Villistas. Black Range Museum |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)